(Re)Direction: Nick Vokey, From Magazines to Mars

/In this sixth installment, I spoke with California-based designer, art director, creative director and showrunner Nick Vokey. Nick hit the ground running with a first design job at The New Yorker and later managed to turn his side projects into an additional career track: Writing and animation. An award-winning animated short he created with a friend eventually developed into the series “Fired on Mars” for HBO Max, and brought similar projects with it. In this conversation, Nick talks about how the similarities between magazines and animation, and what he misses about working in publishing.

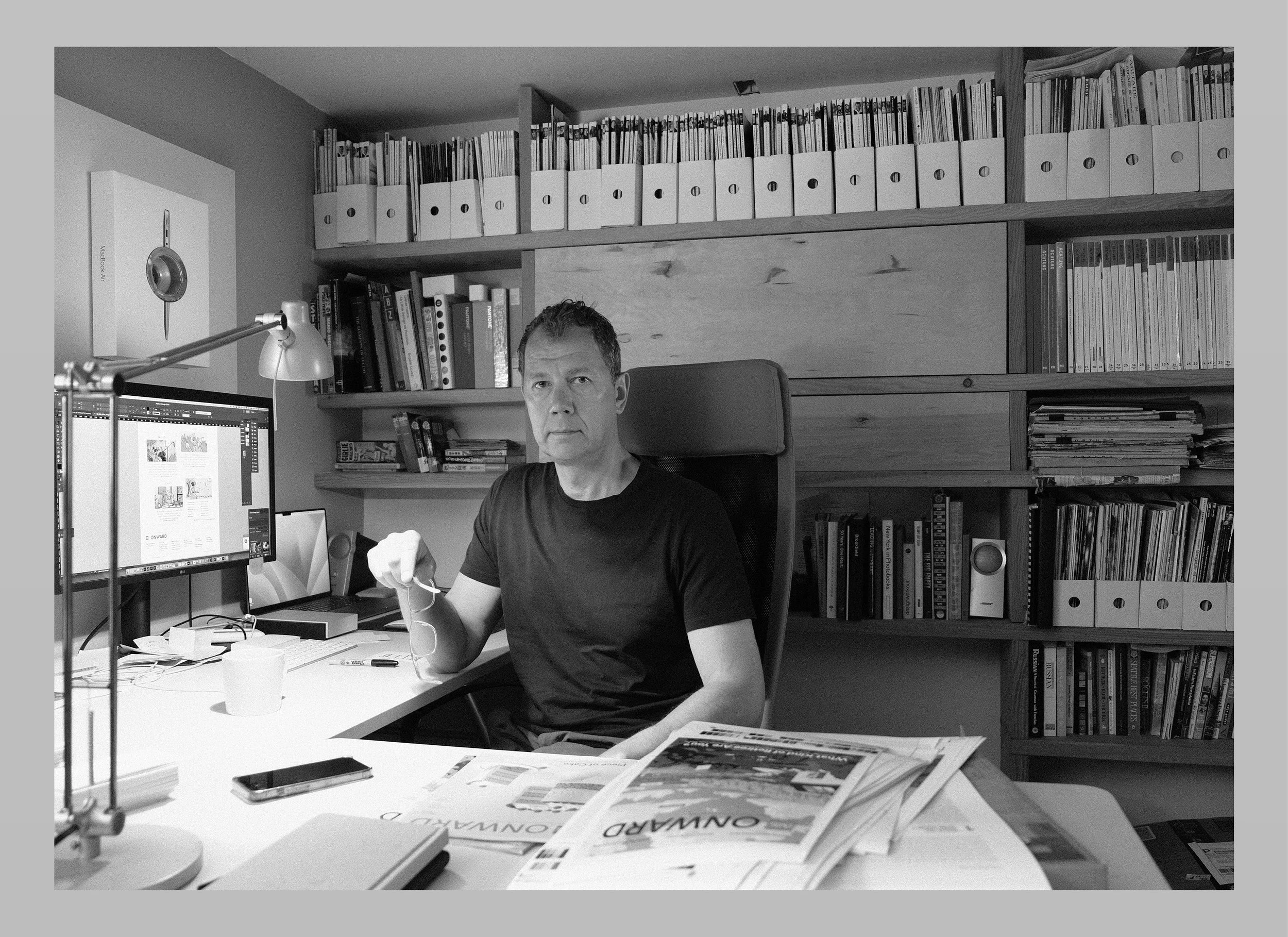

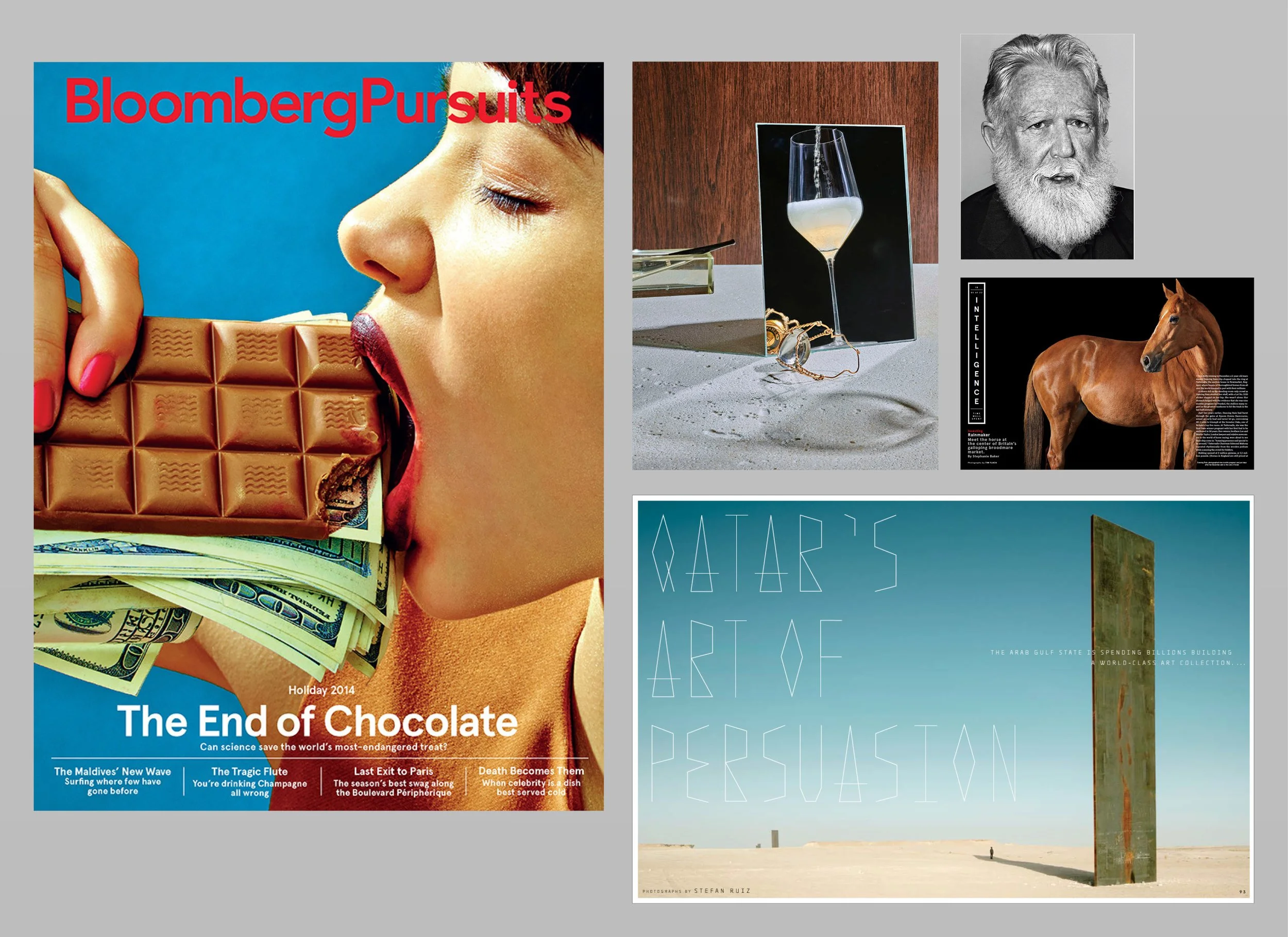

Your editorial-design credentials do not mess around: Your first job was designer and then deputy art director at the New Yorker. From there you went on to do beautiful and smart work at MIT Technology Review as their Chief Creative Officer. Tell me about how you got your start in magazines. Was editorial design something you were always interested in?

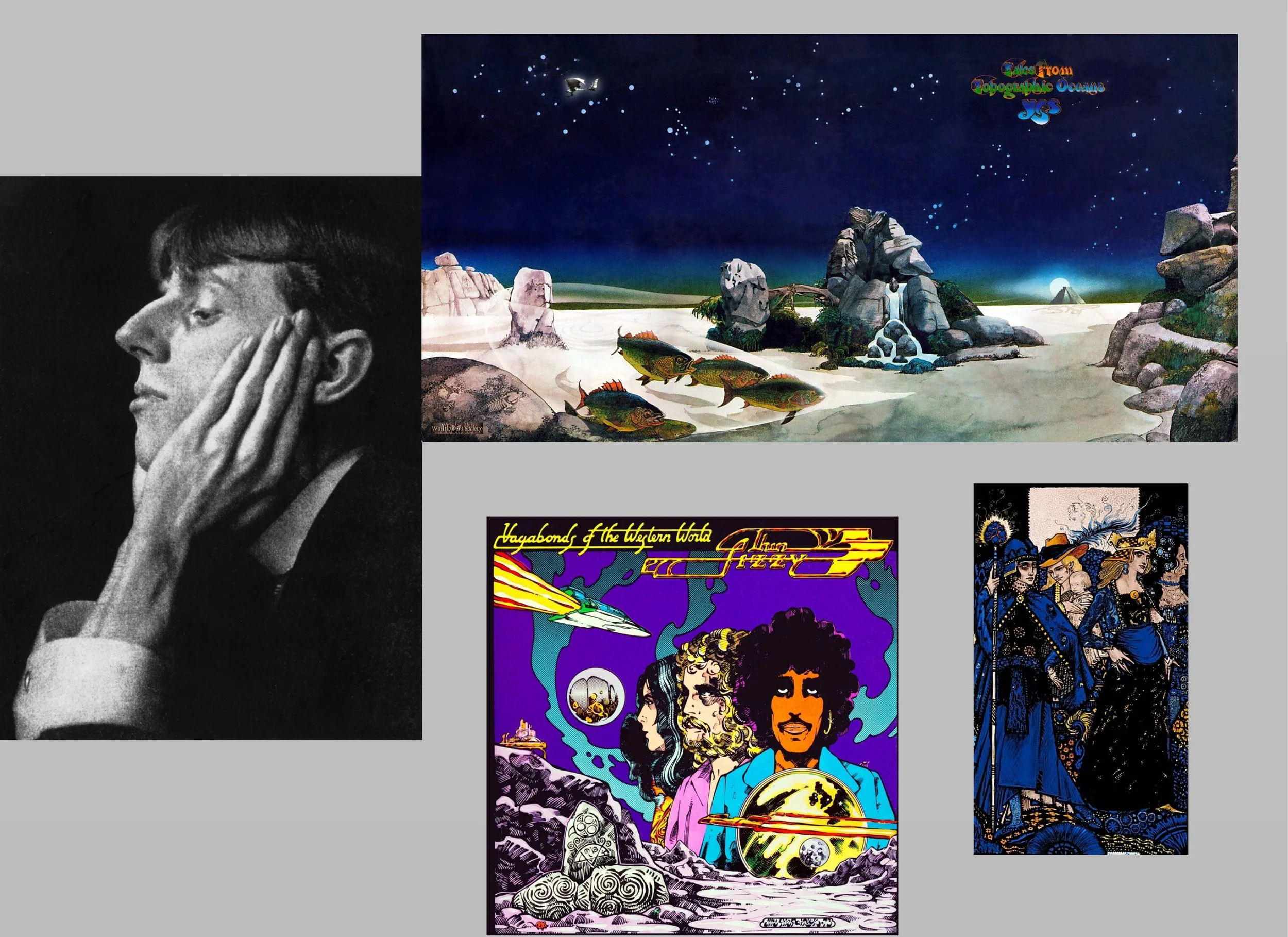

Thank you for the compliment! I was really drawn to magazines as a kid. I'd hang Rolling Stone pages on my bedroom wall, and our downstairs bathroom was wallpapered with old New Yorker covers. I was always drawing and making comics, inspired by magazine artists like Seymour Chwast, Saul Steinberg, and Art Spiegelman. After studying art in college, I moved to New York, worked briefly in a gallery, then unbelievably landed a job at The New Yorker. My first role was the night shift: typesetting, proofing art, updating the wall, and putting the book together. It was perfect training under pressure and great for learning the foundations of creative production. And I had a terrific boss!

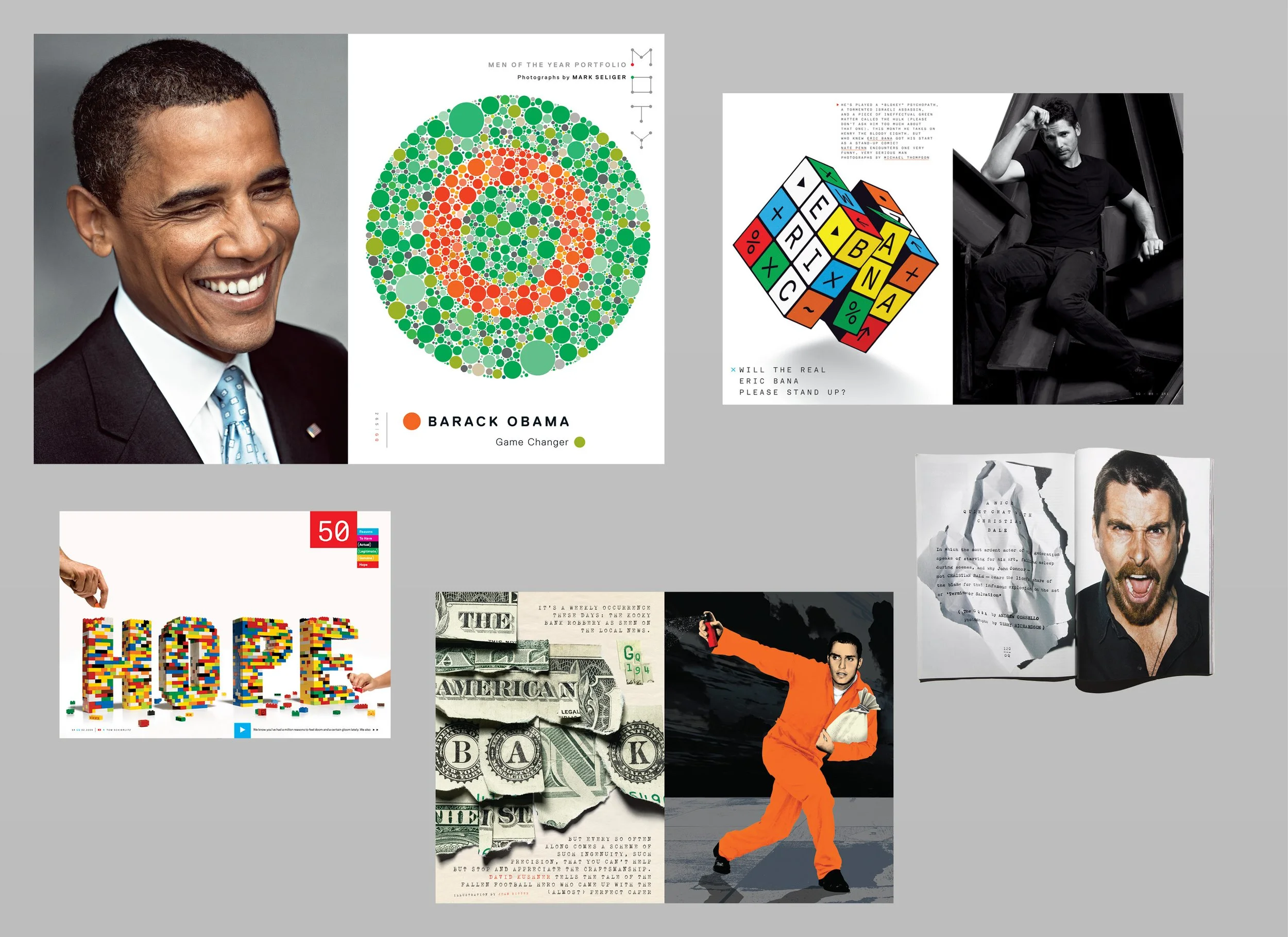

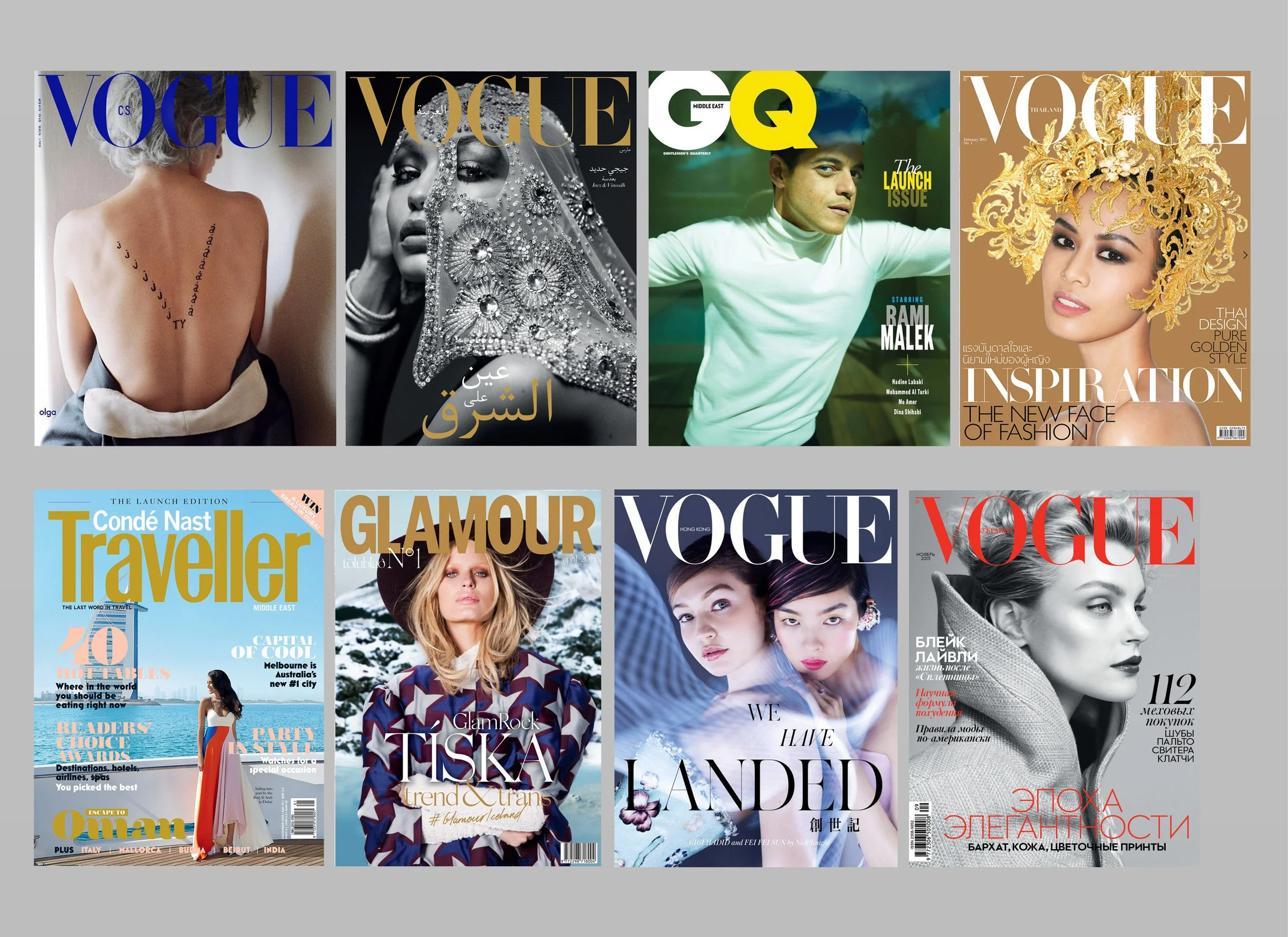

Left from toP: MIT Technology Review cover by R. Sikoryak; The New Yorker art by John Wesley, "The Liar" (1992); Center from top: MIT Technology Review illustration by Thomas Ehretsmann; MIT Technology Review illustration by Jon Han; Right from top: The New Yorker photography by Thomas Struth "Queen Elizabeth II and The Duke of Edinburgh, Windsor Castle" (2011); MIT Technology Review cover by Bendik Kaltenborn; MIT Technology Review illustration by Javier Jaén

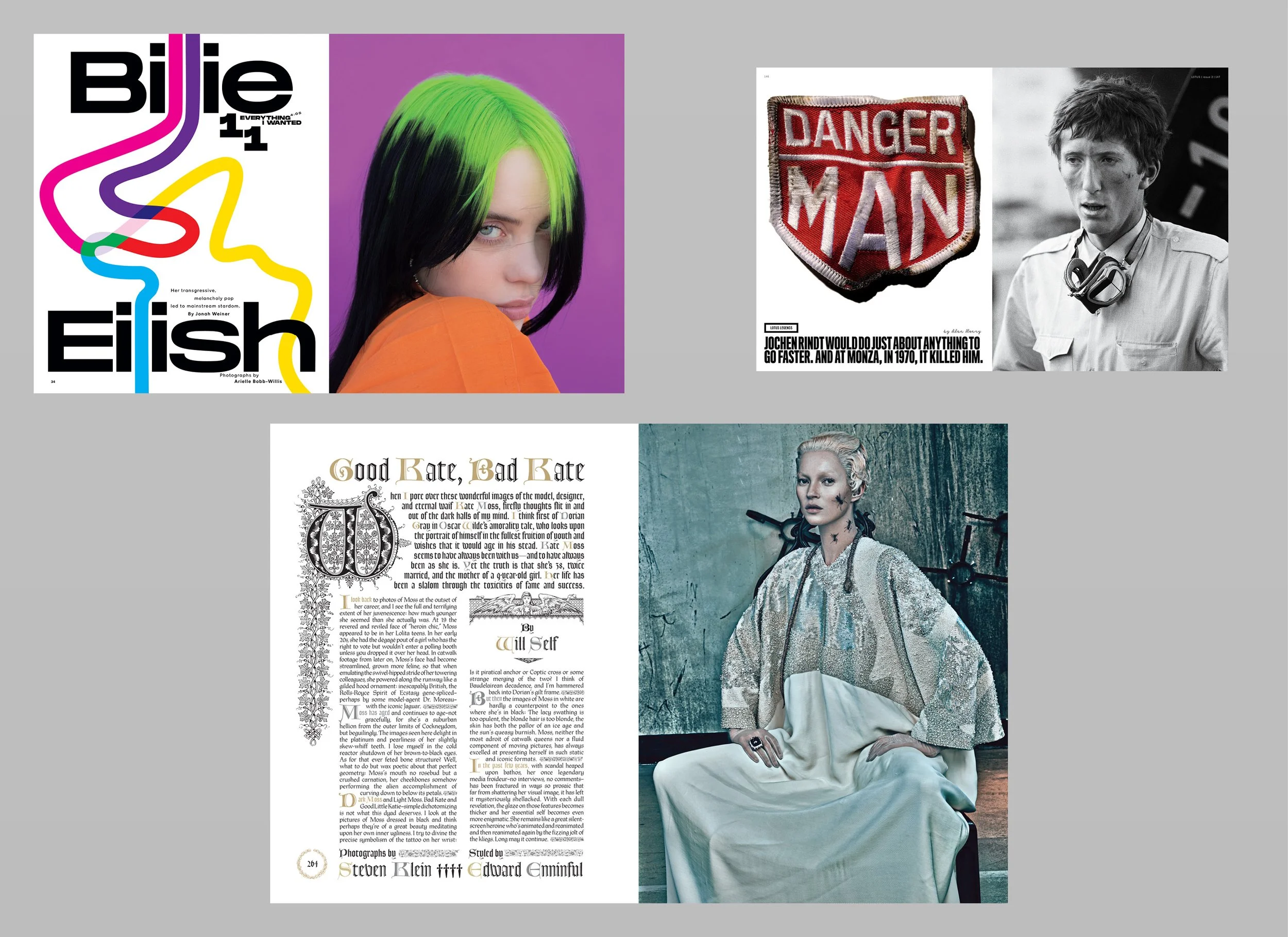

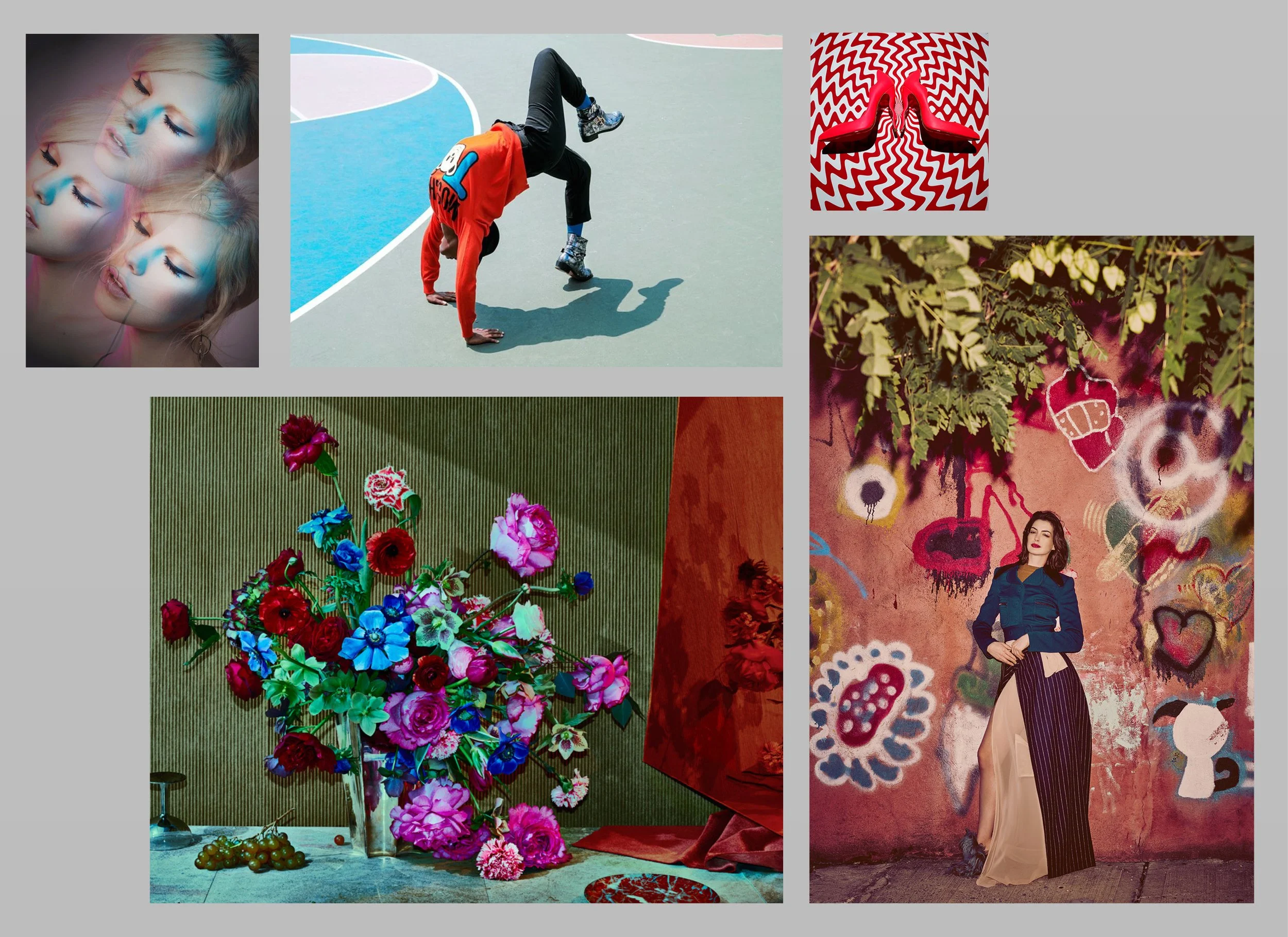

How much of your experiences in the editorial-design world influenced "Fired on Mars", in which Jeff Cooper (a graphic designer) puts all of his eggs in one basket and starts "living his passion" on Mars only to be completely blindsided when he gets fired?

When I started my career in magazines the landscape was shifting rapidly into digital, which created opportunities (and challenges!) for everyone working in publishing. That experience of watching an entire industry transform gave me a visceral understanding of how precarious creative work can be. Jeff’s story captures that anxiety, what happens when you bet everything on a dream job and suddenly the ground shifts beneath you.

Did you hear from any graphic designers or former colleagues who felt that this pretty accurately described their own experiences back here on Earth?

For sure. It's not just creatives. We all know what it's like to have your identity wrapped up in what you do, so losing a job feels like losing part of yourself.

Do you remember a moment when you (or the universe) decided that you might want to change the direction of your career path?

I don’t think I changed. It’s more like I added another track to my career. While working at New Yorker and MIT Tech Review, I was making comics and animated shorts on nights and weekends. Eventually that work started getting attention. “Fired on Mars” began as a short that I made with my friend and collaborator and then when we released it, it won awards at the New York Television Festival and Ottawa International Animation Festival, which helped open doors in the entertainment world.

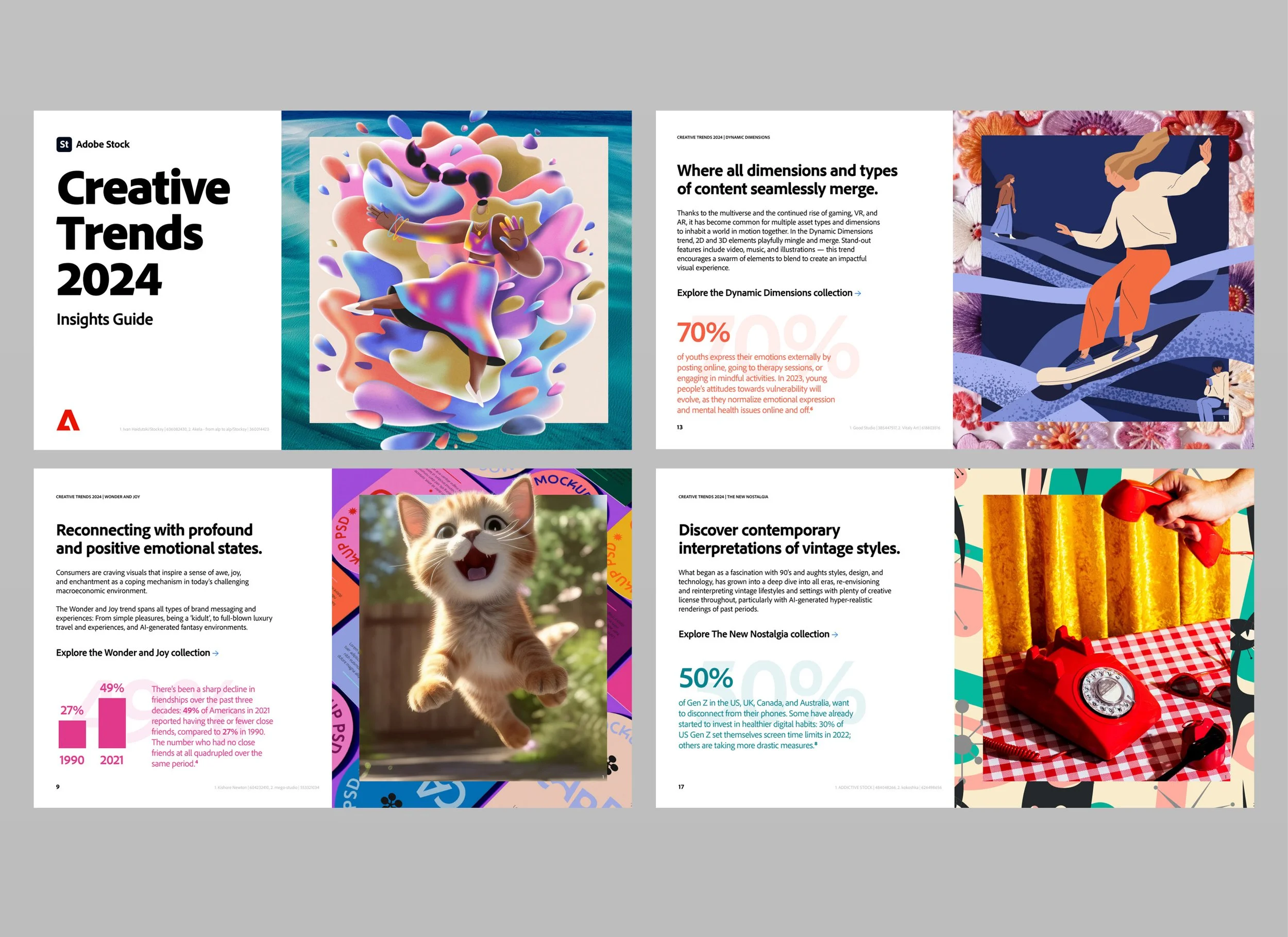

Stills from “Fired on Mars”

How did you bring about and navigate your transition from magazines to television?

Slowly! “Fired on Mars” took years to develop into a series. During that time I moved to L.A., worked at NEO.LIFE (a wonderful online publication that’s sadly no more), got into agency work, and kept building side projects like “Wet City” for Adult Swim. When “Fired on Mars” was finally greenlit, that became my focus.

Are any of the things you learned at magazine publishers applicable to what you are focusing on now?

Absolutely. Both magazines and animation are about storytelling and about managing a complex ecosystem of people and ideas. You’re balancing vision with budgets, deadlines, and resources. The art direction is similar too: in magazines, you pair stories with the right artists; in animation, you translate scripts into worlds. And with both, every single choice is intentional.

The hardest part for both is trusting the process when nothing's working. Mistakes get made, you can’t crack an idea, or something that you thought might work doesn’t and you have to start all over – and as this happens the deadline looms closer! Both taught me that the solution usually comes, but you have to stick with it.

What does a typical work day look like for you?

I recently started developing an animated comedy for a streaming service, so much of my day is writing the pilot. In the morning I’m at my computer writing, in the afternoon I’m collaborating with my writing partner. Sometimes I'll spend time creating artwork for the show, or working on spec projects. I'd also like to take on a new design/art direction project so when I’m not working on the show I've been reaching out to explore opportunities. I love the immediate tactile problem-solving you get to do with design.

Were you ever given any advice (by a mentor or co-worker or anyone, really) that has stuck with you and that you would pass on?

When I was a kid my grandparents had a Burl Ives album with a song “Watch the donut not the hole” which has been stuck in my head for 35 years. I never had any idea what it meant. When David Lynch passed I learned he used to say something similar, “Keep your eye on the donut and not on the hole” and I realized what I think it’s about, which is a combination of ‘focus on what matters and stay positive’, and it’s wrapped up in this friendly surreal folky wisdom. I love stuff like that.

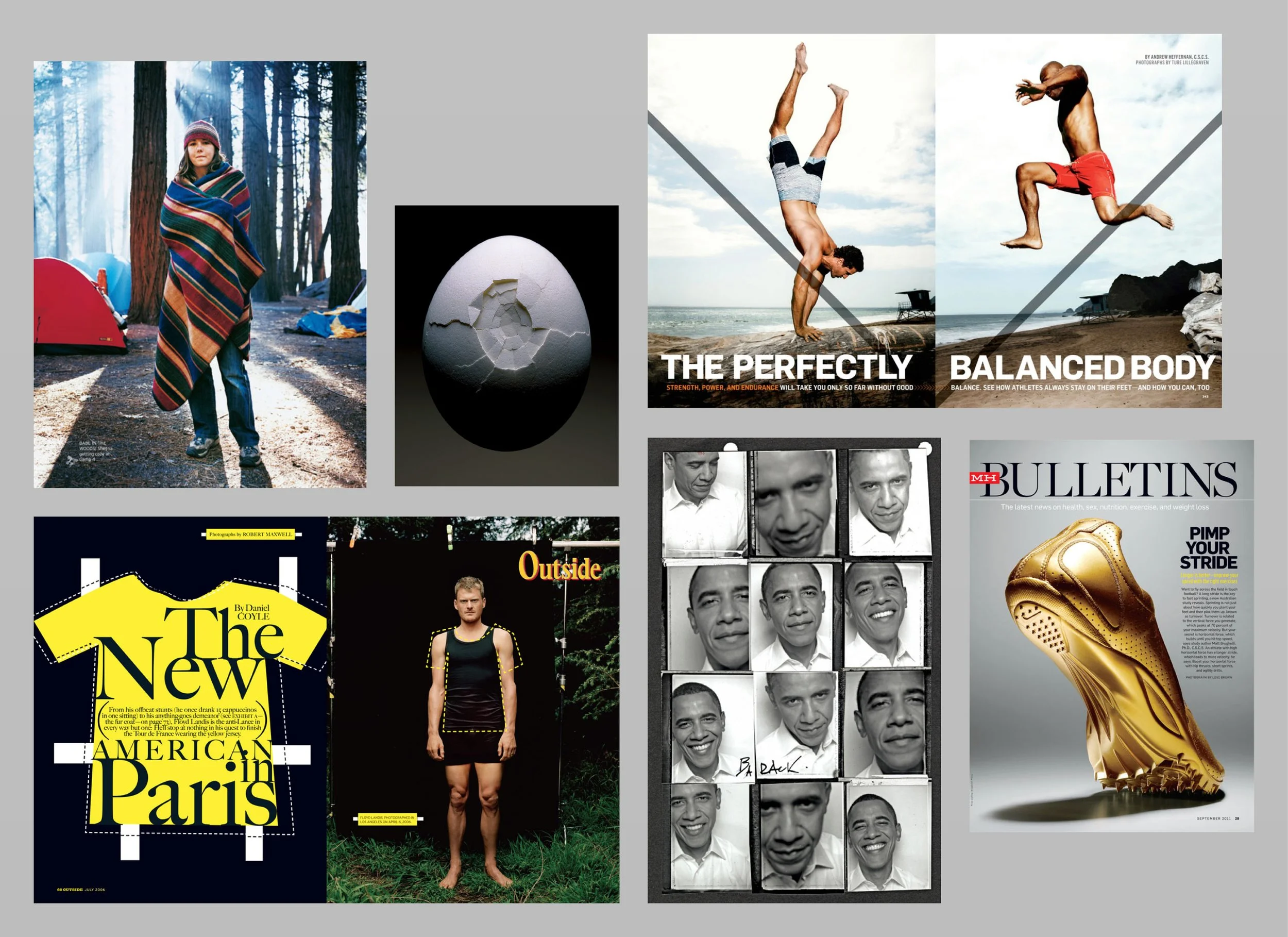

From left: Photograph by Lauren Lancaster; Art by Giuseppe Arcimboldo, "Summer" (1572); Illustration by Paola Wiciak

Looking to the future, what are important stations and/or goals still ahead for you? And is there anything you miss about working at magazines?

With magazines, I miss the culture, the craft, and especially the people. There's something uniquely special about the collaborative nature of editorial: writers, editors, artists, designers, a diverse group of people working together. But it’s also the individuals themselves - I’ve been fortunate to work with so many smart, interesting colleagues and mentors. I also miss being immersed in the world through the work. You're always reading articles, staying current on world events, culture, science, technology - everything. You literally get paid to learn which is amazing.

In terms of the future, I'm excited about the new show I'm working on and there's a new live-action feature I've started writing. I'd also like to take on a design project that challenges me in new ways. I want to stay open. Both kinds of work are about telling stories, with the opportunity and challenge of not knowing what shape they'll take. But when something clicks, and you begin to trust that it will work out, and you start to really see it, it's magic.

For more, head to: work.nickvokey.com